The guerrilla of the 'gavillero

Trujillo's military training and criminal record

February 19, 2017

Indiscriminate repression of the population during the occupation from 1916 to 1924

February 19, 2017

Since it came to life as an independent nation in 1844, the Dominican people have maintained a permanent struggle and with great sacrifice in lives, for the maintenance of its independence and sovereignty.

This explains the immediate attitude of rejection and condemnation of the Dominicans to the 1st U.S. Military Intervention that they suffered between 1916 and 1924, through peaceful civic protests, but also with armed resistance.

The armed resistance against the U.S. military occupation of our country can be said to have begun from the very moment of the arrival of the first U.S. Navy troops, when the teenager, Gregorio Urbano Gilbert, armed only with a revolver, after shouting at the top of his lungs: Long live the Dominican Republic, fired his weapon against a group of U.S. soldiers disembarking at the San Pedro de Macorís dock.

This behavior of armed resistance against the invaders took force almost immediately in the entire eastern region. There, the peasantry, with the support of the inhabitants of the small towns, started a powerful guerrilla movement, which kept the U.S. Army troops in check for several years, forcing them to mobilize permanently, to reinforce them and even to use, for the first time in the world, the use of airplanes for the persecution and bombing of the insurgent zones.

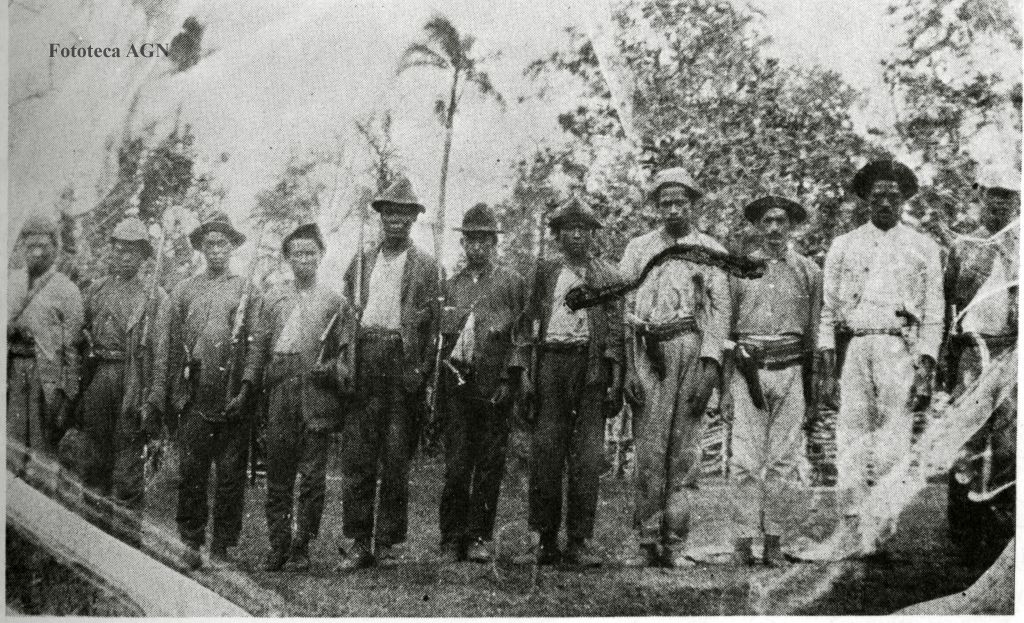

The Dominican people remember with patriotic fervor the names of the main leaders of that heroic resistance, at whose head marched: Vicente Evangelista, (Gilbert joined that guerrilla), Salustiano Goicochea (Chacha), Ramón Nateras, Fidel Ferrer, a school teacher who left the classroom and took up the rifle, and Pedro Celestino Rosario, alias Tolete. For almost a year he was the scourge of the occupying military forces, achieving a strong leadership in the region, as he defeated the U.S. troops that pursued him on more than ten occasions.

The powerful columns of the patriotic resistance movement, which the Americans contemptuously called “gavilleros”, reached such a degree of efficiency in the combat against the invaders that the officers could not find any explanation for the large number of casualties they suffered, and therefore, alarmed, they came to believe that the Dominican guerrillas were advised by foreign experts.

For example, in 1918, the magnitude of the guerrilla expansion of the East reached such levels that Lieutenant Colonel Thorpe, military chief of that entire region, wrote a lying report to his superiors stating: “The German supporters and advisors of the insurrectionists have not been sleeping and have made every effort to strengthen and keep alive this livel.

By the end of 1918, guerrilla actions had grown in number and effectiveness in their combats against the invaders, which forced the invaders to further increase the number of their troops and establish permanent hospitals to care for the wounded in San Pedro de Macorís, El Seybo and La Romana.

They also sent to the area a corps of spies and assistants brought from Puerto Rico, and some Dominicans who joined their recently created “National Guard”, among them Rafael Leonidas Trujillo, where he began his long criminal career against his homeland.

The rebellion against the interveners in the eastern region was kept alive for several years and began its decline when information came to light in our country indicating that the U.S. government was willing to begin talks to establish an evacuation plan in the short term, which was finally achieved in 1924.