U.S. Military Dictatorship.1916/1924

2nd U.S. Military Intervention

February 18, 2017

The creation of the Dominican National Police - National Army

February 19, 2017The first two dispositions taken by the military government established by the United States in the Dominican Republic, published simultaneously with the proclamation of the occupation, were: the one prohibiting the carrying and possession of arms, projectiles and explosives, and the one subjecting all publications to the strictest censorship. In the latter order, the military government decreed the prohibition of any kind of “commentary on the attitude of the United States, and anything in connection with the occupation”. The measure was also extended to telegraphic and cable communications.

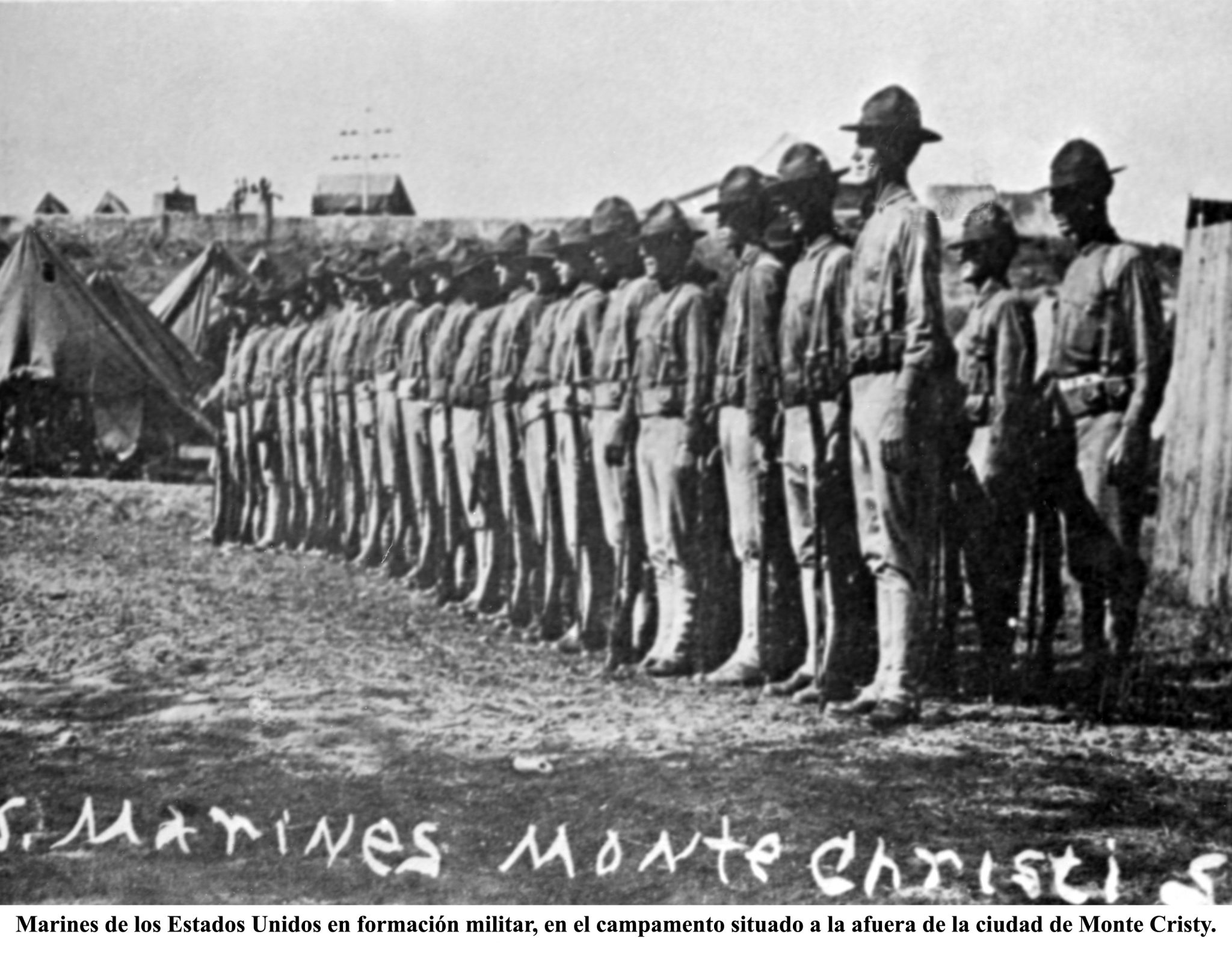

As soon as he arrived in the occupied country, the American Minister informed his superiors that the military intervention was accepted by the generality of the people and that “the disillusioned politicians were the only dissatisfied people”. To tell the truth, the proclamation of the occupation surprised the traditional politicians, because except for the small rebellion led by General Manuel de Jesus Perez Sosa, governor of the Pacificador province, and other attempts in Azua and Salcedo, the months of November and December 1916 passed without great difficulties for the occupiers.

The behavior observed by the traditional politicians and intellectuals, representatives of the petty bourgeoisie, the landowners, the large wholesale import and export trade in the face of the US military intervention, was very different from that of the peasantry of the eastern region. A good part of the first ones simply accepted it, hoping that it was a passing evil, as was the case of Federico Velásquez, who on December 7, 1916 expressed that the military occupation did not represent “immediate or ulterior danger for the independence of the country”; another group, in principle a very small minority, entered in frank collaboration with the foreign interveners occupying important positions, and another small fraction, decided to confront the invader by means of peaceful civic actions without making an effort to establish links with the peasant guerrilla movement. Among the latter group was the president himself, deposed by the occupiers, Dr. Francisco Henríquez y Carvajal.

From 1916 to the beginning of 1919, only the patriotic guerrilla forces of the eastern region confronted the invaders.

.The situation, however, began to change after the end of the First World War. In 1919, a hidden but strong nationalist movement of agitation began in the country, stimulated by the entry into circulation of loose sheets calling on the people to break apathy. A great part of these loose sheets and bulletins came from Cuba. They contained journalistic articles written by President Henríquez, the poet Cestero and other patriots based there. By this time the “Dominican Nationalist Commission” had already been founded in New York, presided over by President Henríquez, and which included his son Max, and the poet Tulio M. Cestero.

In mid 1920, the Military Governor, through Executive Order No. 385, repealed prior censorship, but prohibited any oral or written expression of ideas “hostile or contrary to the Military Government”. This created a small opening that the Dominican intelligentsia took advantage of to publish a series of articles, loose sheets and pamphlets against the interveners.

The U.S. dictatorship responded to the challenge by submitting the main perpetrators to trial by military court, whose all-powerful powers were identical to those of a court martial. Américo Lugo, the poets Fabio Fiallo and Sanabia and the journalists Doroteo Regalado, Oscar Delanoy, and others were subjected to this court.

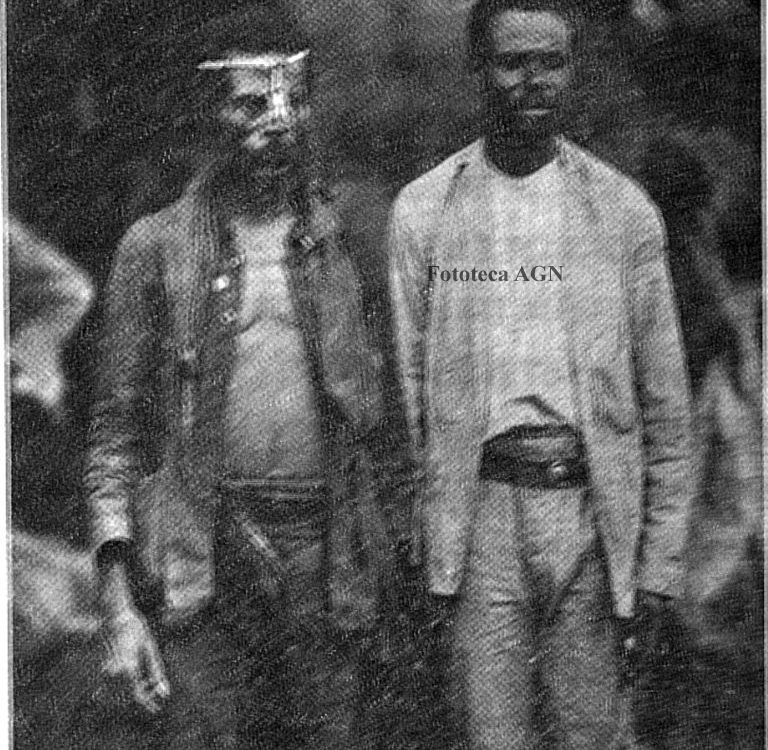

To these persecutions was added another one that created a new scandal of the same proportions: Venezuelan journalist Horacio Blanco Fombona published in November 1920 in Letras magazine a photo of a Dominican peasant named Cayo Baez, showing the wounds and burns received on his chest as a result of the torture to which he was subjected by U.S. soldiers for his refusal to give up the names of other companions of his who were against the military intervention.

As a result of these events, the Dominican cause began to occupy a significant space in the Latin American press, but especially in Cuba, Chile, Argentina, Mexico, Uruguay and Central America. International solidarity, on the one hand, and the efficient patriotic work carried out by the Dominican National Union, on the other hand, as well as the actions developed by the peasant guerrillas of the Eastern region, were creating a new situation in the Dominican Republic. In September 1920, Governor Snowden himself admitted the existence of a state of “hostility among the people”.

The slogan raised by the members of the Dominican National Union and the Nationalist Junta was raised throughout the Dominican territory: “Evacuation pure and simple”.

The North American occupants built several hundred kilometers of highways that linked the capital city with the main agricultural centers of the country; they also built several prisons, public buildings for official offices, schools, fortresses, markets, and rebuilt the docks of Santo Domingo, San Pedro de Macorís and Puerto Plata, with the help of dredges that were acquired during the Cáceres government. In terms of sanitary constructions, the military government inaugurated two hospitals and a leprocomio. Both the North American sugar and lumber estates continued to grow in an overwhelming manner, reaching a total of six million tareas of land under private control or ownership. Another important element that caused changes during the U.S. occupation was the banking and financial sector, which deepened the process of penetration and domination of monopoly capital in the Dominican Republic.